“The saddest sight of desolation”

By Wednesday morning the strong winds that had so helped the fire to spread across the City had begun to die down. But most of the city was already destroyed, and some areas were still suffering new fires. Here we present key details from the fourth day of the Great Fire of London.

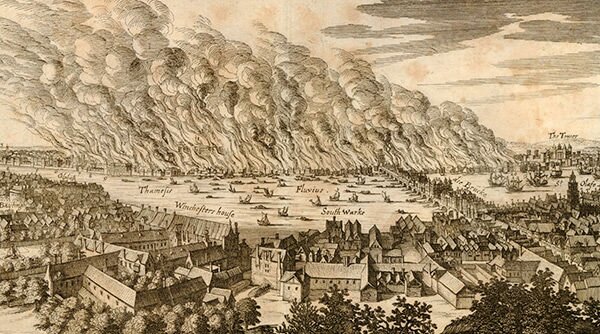

Above: Detail from a Dutch etching depicting the great fire seen from the south side of the Thames, anonymous artist, 1666 © Trustees of the British Museum.

2:00 a.m. – the time Pepys was woken by his wife, reporting new cries of “Fire!”. Pepys, his wife and a young friend, Will Hewer, made their escape by boat to Woolwich.

£2,350 – the value of gold, his life savings, that Pepys took with him (having already moved most of their possessions to safety).

6:00 a.m. – the time the king evacuated Whitehall, leaving for Hampton Court.

6:00 a.m. – the approximate time the Duke of York returned to the streets, first inspecting the area around free Street and then heading north towards Cliffords Inn, where he organised men, women and children in the salvage of the Court records from the rolls Chapel.

7:00 a.m. – the time that Pepys arrived back in London (leaving his wife and Hewer in Woolwich, guarding his gold). Pepys found his home in Seething Lane had survived intact (due to the blowing-up of nearby houses to create a firebreak), before climbing the steeple of Barking Church to survey the scene.

There was the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw. Everywhere great fires. Oyle-cellars and brimstone and other things burning. I became afeared to stay there long, and therefore down again as fast I could. – Samuel Pepys.

12:00 p.m. – the approximate time the fires around Holborn Bridge were extinguished.

4 – the number of engineers recruited to assist seamen in the creation of firebreaks at Temple, including the shops adjoining the ancient Templars Church, which was saved as a result.

1 sovereign – the amount paid to each engineer.

Bread, beer, meat, all in scarcity and many want it. – Dr William Denton, physician to King Charles II.

2 pence – the amount Pepys paid for a one pence loaf when visiting the makeshift refugee camp in Moorfields.

50,000 – the number of French and Dutch said to be heading toward the refugees in the fields outside the city walls to “cut their throats and spoil them of what they save out of the fire” (Thomas Vincent). This led to panicked and angry mobs heading back into the city, armed with whatever was to hand, to attack foreigners.

Did You Know?

The paranoia about the fire being a deliberate act of terrorism spread far beyond London. On the Wednesday, a butcher moving oxen through the centre of Oxford and shouting “Hiup! Hiup!” to hurry them along, had his cries misheard as “Fire! Fire!”, causing frightened worshippers to run from a nearby church, convinced that they could smell smoke.

10:00 p.m. – the time that one seaman, Richard Rowe, climbed onto the burning roof of the Middle Temple Hall to beat the flames out.

£10 – the award given to Rowe for his brave efforts.

1 – the number of fires that remained alight on Wednesday evening, in the area around Bishopsgate, which was finally extinguished shortly before dawn after Pepys was instructed to lead a team of seamen there.

The only persons who derived benefit from the calamity were those who had nothing to lose. Beggars, the cut-purses, the predatory tramps, the nocturnal prowlers, availed themselves to the full of the opportunities which the darkness and desolation around now offered them. – Alexander Charles Ewald, ‘The Great Fire of London’, Gentlemen’s Magazine vol 250, 1881.