“Burning up the very bowels of London”

By Tuesday morning the fire had doubled in size and around half of the City had been destroyed. The fire was now at it’s peak, “burning up the very bowels of London” (Thomas Vincent). Read on for the key facts from the third day of the Great Fire of London.

Above: Map showing the extent of the fire at the close of Tuesday (arrow points to Pudding Lane, where the fire started).

5:00 a.m. – the approximate time that the King Charles II and the Duke of York rode through the city to give encouragement to people fighting the fire.

100 – the number of guineas that the king carried with him, to distribute as a reward and an incentive to those fighting the fire.

6:00 a.m. – the approximate time that the order preventing carts from entering the city, put in place the previous day, was withdrawn.

12:00 p.m. – the approximate time the Duke of York was almost overcome by heat when the buildings behind him were set alight. He and the men working around him had to flee for their lives.

The flames quickly cross the way by the train of wood that lay in the streets untaken away, which had been pulled down from the houses. – Thomas Vincent, describing the futile efforts to fight the fire, as wood left when buildings were pulled down simply allowed the fire to spread across the gaps created, ‘God’s Terrible Voice in the City’, 1667.

12:00 p.m. – the approximate time that fire reached Ludgate and Newgate, destroying the prisons.

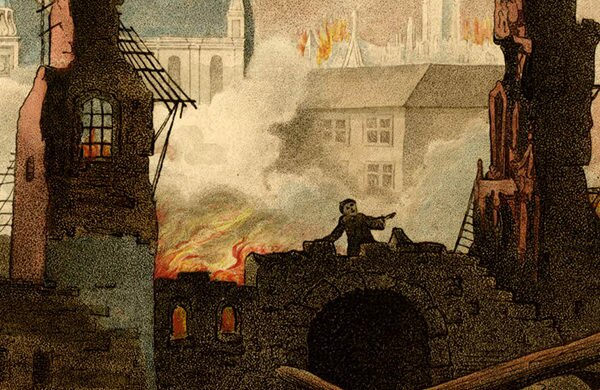

Above: Detail showing Ludgate prison destroyed by the fire, from an etching by William Russell Birch, 1792 © Trustees of the British Museum.

5 miles – the distance at which ‘the half burnt leaves of books’ were seen west of the city, in Acton.

20 miles – the distance at which pieces of burnt paper were seen, in Windsor Great Park and Eton.

30 miles – the distance at which scraps of scorched silk were found, in Beaconsfield, west of London.

Did You Know?

The sheer heat of the air ahead of the fire left buildings so scorched that they rapidly succumbed when the flames did finally reach them, causing entire streets to burn within minutes of the fire’s arrival.

£40 – the amount one Yeoman, John Broomfield, was paid for moving some of the coal stored at Bridewell, a hall near the waterfront, before the flames reached the building.

£300 – the amount paid for lumps of molten silver found in the ruins of the Merchant Taylor’s Hall, to the north of the city.

£446 – the value of coins left behind in Draper’s Hall, which when recovered, had melted and could only be sold for scrap value. Gold and silver plate from the same property was saved, however, by dropping it into a sewer below ground.

£100 – the amount paid out by one Alderman, in gold, to people to save his building by pulling down the properties around it.

£10,000 – the value of a chest of money rescued from property of one wealthy Londoner, Sir Richard Browne.

£4 – the amount he rewarded the men who saved it.

30 – the number of men who worked to save Sir Samuel Starling’s property in return for a reward.

2 shillings, 6 pence – the amount that Starling gave to be shared between all of the men who saved his property.

6:00 p.m. – the time the fire reached Temple.

Did You Know?

When he arrived to find the Middle Temple Hall on fire, the Duke of York also discovered the gates had been locked through fear of looters. This prevented his men from gaining access to fight the fire, so that when the gates were finally opened the hall could not be saved.

100 yards – the approximate distance from the fire at which the heat was found to be intolerable, such was the intensity of the flames.

18 – the approximate number of hours the Duke of York was engaged in fire-fighting efforts on the Tuesday, “so active and stirring in this business, he being all the day long, from five in the morning till eleven or twelve at night, using all means possible to save the rest of the city and suburbs” (letter from Sandys to Scudamore, quoted in ‘The Dreadful Judgement’, Neil Hanson, 2001).

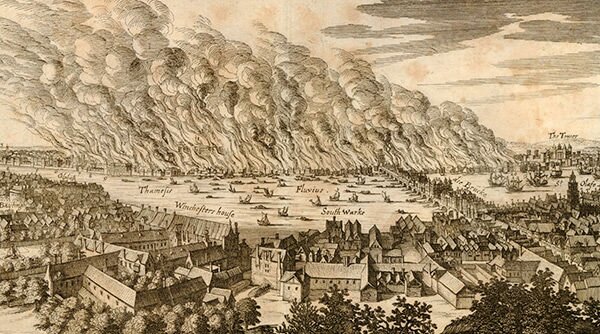

Above: A detail from a contemporary German etching showing an impression (somewhat exaggerated) of the fire viewed from the southern side of the Thames © Trustees of the British Museum.

260 – the number of children who had to evacuate the school at Christ’s Hospital in the north of the city.

14 months – the time it took for Christ Church to recommence schooling.

10:00 p.m. – the approximate time that buildings in the area of Somerset House were pulled down, in an attempt to save Whitehall.

200 yards – the approximate distance that the frontline of the fire was from Somerset House.

11:00 p.m. – the approximate time at which the strong winds that had been fanning the flames finally began to die down, giving the first real hope that the fire might be stopped. However, it also changed direction, and started to drive the fire south towards the Tower of London.

600,000 lbs – the approximate weight of barrels of gunpowder stored in the White Tower of the Tower of London. If it had ignited it would have not only destroyed London Bridge but “sunk and torn all the vessels in the river and rendered the demolition beyond all expression for several miles about the country” (John Evelyn). As the fire approached, desperate efforts were made to get the gunpowder barrels onto ships, to be moved downstream away from the fire.

£1,200,000 – the value of money, gold, silver and jewels moved to the Tower by London’s goldsmiths and so needed to be moved again, carried by barge to Whitehall.

Did You Know?

To save the Tower, gunpowder was used to blow up surrounding houses, including those along the full length of Watergate as well as a wine warehouse on Seething Lane (the street where Pepys lived). The timber from these demolitions was thrown into the Thames.