“Now hopes begin to sink”

Initially considered to be just another fire in a city where fires were commonplace, the conditions – a long drought, strong winds and a city full of flammable buildings and goods – meant that this blaze spread quickly. By the afternoon hundreds of houses were alight. The concerns of Londoners grew; first for the safety of their property, then due to wild rumours of a French or Dutch attack, and by evening into a general panic to evade the advancing flames. Read on for key facts from the first day of the Great Fire of London.

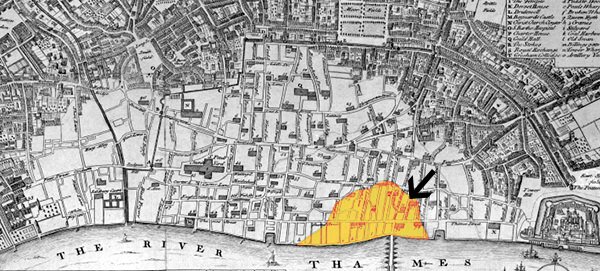

Above: Map showing the extent of the fire at the close of Sunday (arrow points to Pudding Lane, where the fire started).

10.00 p.m. – the time the previous evening that Thomas Farriner – the owner of the Pudding Lane bakery where the fire started – claimed he had extinguished the bakehouse oven, raking up the coals before retiring to bed.

12.00 a.m. – the time Farriner claimed to have returned to the oven to find that it no longer offered enough heat to light his candle.

1:00 a.m. – the approximate time that the fire, which started in the bakehouse oven, was discovered by Farriner’s manservant.

Did You Know?

Whilst others had time to gather their valuables and attempt to get them to safety, Thomas Farriner lost everything in the fire. Even his gold, which he later dug out of the ruins as a molten block, could only be sold for the weight of the metal.

4 – the number of people in the bakery on Pudding Lane on the night the fire started; Thomas Farriner, Hannah (his daughter), Teagh (his manservant), and a maid.

3 – the number of the occupants who managed to evade the fire – Thomas, Hannah, and Teagh – by escaping over the rooftops of neighbouring houses. A maid was too scared to follow them and perished in the fire, becoming the first victim.

40 feet – the height of the roof of the Pudding Lane bakery, along which Thomas, Hannah and Teague escaped before climbing through the garret window of a neighbour, Robert Taniton.

23 – Hannah Farriners age at the time of the fire.

Did You Know?

Although she escaped alive, Hannah was badly burned about her face and arms.

13 Aug 1671 – the date Hannah Farriner died, not long after giving birth to her third child (in 1667 she married Nicholas Day, also a baker).

5 – the number of years after the fire that Hannah died.

30 minutes – the approximate length of time that the fire was initially confined to Farriner’s house, before finally spreading, first to neighbour Taniton’s house, and then on along the lane.

1 hour – the approximate time after the fire was discovered that the parish constables arrived at the scene, where they observed that the spread could only be prevented by demolishing the adjoining houses, a common firefighting technique in seventeenth century London. However the householders of those properties objected and so the Lord Mayor Thomas Bludworth was summoned.

3:00 a.m. – the time that the diarist Samuel Pepys was woken by his maid, Jane, to tell him of the fire. Pepys, seeing the flames were at the lower end of the neighbouring street, went back to sleep.

Did You Know?

Warehouses on Thames Street alongside the river were full of highly flammable materials, a “most combustible matter of tar, pitch, hemp, rosen and flax” (anonymous). This meant the fire could spread quickly and easily, and prevented access to the very water needed to help put out the fire.

The lodge of all combustibles. – Edward Waterhouse, a London preacher, describing the wharves alongside the north edge of the Thames.

7:00 a.m. – the time that Pepys arose from his bed.

300 – the number of houses estimated to have burned down by the morning, according to word passed to Pepys by his maid.

1 hour – the time that Pepys spent watching the fire, and peoples’ reaction to it, first from the Tower of London and then by boat from the Thames.

11:00 am – the approximate time that Pepys, alarmed by the extent and rapid spread of the fire, arrived at Whitehall to see King Charles II.

Did You Know?

The King asked Pepys to travel to Lord Mayor Bludworth to instruct him to pull down buildings to create a fire break. He gave Pepys a parchment to pass to Bludworth, authorising him to “spare no houses but pull down before the fire every way”. Bludworth dithered, however, and eventually Charles himself had to sail down from Whitehall to give orders.

11:00 am – the approximate time by which a rumour had begun to spread that French and Catholic residents had started attacking, leading panicked people to begin arming themselves with whatever was to hand.

4,000 – the number of French and Catholic said to be attacking London.

The ignorant and deluded mob, who upon the occasion were hurried away with a kind of frenzy, vented forth their rage against the Roman Catholics and Frenchmen, imagining these incendiaries (as they thought) has thrown red hot balls into the houses. – William Taswell.

2:00 pm – the approximate time that Pepys caught up with Lord Mayor Bludworth, in Canning Street.

Did You Know?

When Pepys found the Lord Mayor, Bludworth had already organised men from the Trained Bands to start pulling down houses, despite opposition from their owners.

3:00 p.m. – the approximate time that the roof of the Pudding Lane bakery finally fell in, sending sparks into the sky.

3:00 pm – the approximate time that King Charles II, accompanied by his brother, James, Duke of York, sailed down the Thames to observe the fire.

200 yards – the distance that one blazing ember was carried on the wind, from the bridge and across the river, to ignite a fire at a stable in Horseshoe Alley in Southwark. It set two adjoining houses ablaze before the fire was brought under control by the creation of a firebreak.

Did You Know?

Instead of helping to fight the fire, many residents in and around Pudding Lane spent the time moving their belongings to nearby Saint Margaret’s on Fish Street Hill, where they thought their valuables would be safe from the fire. Instead, Saint Margaret’s succumbed to the flames within hours.

5 – the number of times some people were said to have moved their possessions, each time having to move again as the place they thought safe was finally overtaken by the fire.

3 furlongs – the distance (600 m) that embers were being carried on the wind, according to the account of William Taswell, then a schoolboy at Westminster School.

I myself saw great flakes carried up in to the air at least three furlongs. These at last, picking up and uniting themselves to various dry substances, set on fire houses very remote from each other. – William Taswell.

14 – the age of William Taswell (c. 1651–82) at the time of the fire, a schoolboy at Westminster School, whose memoirs have also added to our understanding of the Great Fire.

100 – a contemporary estimate of the number of houses being burnt every single hour by Sunday afternoon.

Did You Know?

When the fire began to spread, as many people as were in a position to do so took themselves and their goods onto the Thames in boats, lighters and skiffs.

300% – the increase in the cost boatmen charged to carry people to the southern shore of the Thames.

The streets full of nothing but people and horses and carts loaden with goods, ready to run over one another, and removing goods from one burned house to another. – Samuel Pepys, describing the city on the Sunday evening.

3 – the number of houses that had burnt to the north of the Pudding Lane bakery some 14 hours into the blaze (4:00 pm). So strong were the winds blowing from the north east that the fire had only inched along in the opposite direction.

8:00 pm – the time that the blaze reached and engulfed the Three Cranes Tavern, from where the king had earlier viewed the then distant fire.

3 – the number of distinct areas of fire burning by the evening, which then re-joined to become fiercer still.

Did You Know?

By the Sunday evening, people who had stored their goods for safe keeping in the churches around Cannon Street realised this was no longer safe and had to move them again, further north to Cornhill.

Now hopes begin to sink, and a general consternation seizeth upon the spirits of people: little sleep is taken in London this night. – Thomas Vincent, ‘God’s Terrible Voice in the City’, 1667.