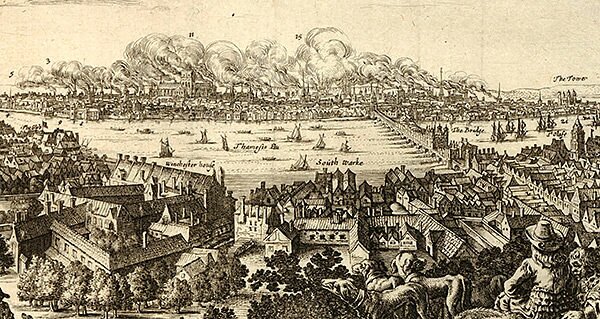

“London is shattered and broken to pieces”

With more than 80% of the City of London destroyed by fire (13,200 houses alone), and a similar percentage of the population rendered homeless, there was an urgent need to rebuild the city and to recommence trade.

Various ambitious plans were put forward for the design of a new city, and whilst these were largely rejected, some property owners would still lose land in the rebuilding as streets were widened or redesigned.

The greatest financial burden looked likely to fall on the very victims of the fire, however, and so moves were made to ensure the burden was better shared. At the same time new regulations were imposed to ensure the new properties would be less susceptible to fire in the future.

Above: © Trustees of the British Museum.

London is now fled away like a bird, the trade of London is shattered and broken to pieces… – Thomas Vincent, ‘God’s Terrible Voice in the City’, 1667.

6–8 months – the period after the fire that the rebuilding is likely to have commenced, in the spring of 1667.

800 – the approximate number of buildings rebuilt in 1667.

12–15,000 – the approximate number of buildings rebuilt by 1688.

Did You Know?

Since mediaeval times, the City of London had placed a tax on coal imported into London via the Thames. After the Great Fire, this tax was used to fund the rebuilding of public buildings.

12 pence – the tax (one shilling) payable on each ‘tun’ of coal brought into London.

£50,000 – the approximate amount of money raised by the tax on coal.

200 years – the length of time the new coal tax continued, long after the rebuild was completed.

0% – the percentage of Londoners who had insurance against the fire; it did not exist then.

14 years – the period after the great fire that London’s first fire insurance company appeared (in 1680).

Did You Know?

Rebuilding private buildings was financed by their leaseholders, whilst public buildings were largely financed by a tax on coal.

10 September 1666 – the date the Kings Council (sitting with the City aldermen, magistrates and ‘citizens of quality’) issued an order that inhabitants of ruined property must first clear the debris from the street in front before commencing reconstruction work on their own property.

11 September 1666 – the date the committee met for the first time to allocate temporary rights to tradesmen and craftsmen, to use empty spaces to recommend their businesses.

13 September 1666 – the date a new royal proclamation was issued prohibiting rebuilding until new regulations had been formulated and issued.

3 – the number of major project proposals put forward for the rebuilding of London (proposals from Evelyn, Hooke, and Wren – see panel).

The Proposals

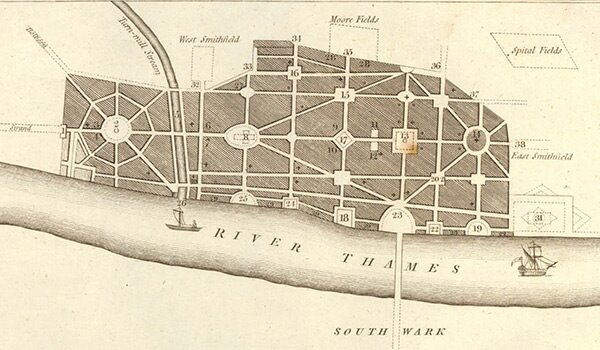

John Evelyn – a royal adviser and horticulturalist, Evelyn’s plan (presented directly to the King sometime around 13 September 1666) called for the rebuilt city to reflect a grand and graceful garden, with piazzas located throughout and with St Paul’s as the centrepiece. The city would be unpolluted, with noxious trades moved outside of the city walls and the Port of London relocated to the south bank of the Thames). Streets would be wider too, no less than 100 feet across for London’s principal streets, and no less than 30 feet across for the narrowest, minor streets.

Robert Hooke – curator of experiments at the Royal Society, Hooke was also a specialist in the field of geometry. His plan (presented 21 September 1666) was for a geometric grid of exact squares, aligned north south east and west. It required a complete redesign of the damaged area, erasing the old streets completely. He was appointed a city surveyor for the rebuild, effectively Wren’s assistant. Hooke was a talented but not widely-liked individual, once described as ‘the most ill-natured and self-conceited man in the world’.

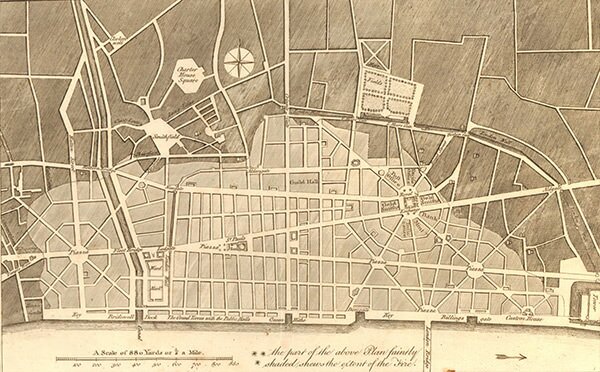

Christopher Wren – a professor of astronomy, Wren was appointed to be King’s Surveyor of Works. He was considered by some to be something of a genius (at the age of 22 he was described by Evelyn, a fellow student at Oxford, as ‘that miracle of a youth’). The plan Wren put forward was also geometric in nature, but with angular roads fanning out from squares, and with a repositioned (and cleared) London Bridge. He also with St Paul’s Cathedral as the centrepiece.

Above: John Evelyn’s plan for rebuilding London © Trustees of the British Museum.

Above: Christopher Wren’s plan for rebuilding London © Trustees of the British Museum.

Did You Know?

None of these plans were accepted. They each involved erasing the old street plans and starting afresh, but of course those streets, whilst lying in ruins, nonetheless represented plots of land that people owned. The legal difficulties of revoking freeholds, of allocating out the new properties, and the significant costs of compensating owners and tenants proved too big a challenge.

£5,000 – the maximum cost of rebuilding the Royal Exchange, if materials from the old building were recycled, as estimated by Robert Hooke; his proposal was rejected however.

£60,000 – the approximate actual cost of rebuilding the Royal Exchange, using new materials and a more extravagant design proposed by Edward Jerman. The resultant debt almost bankrupted the Mercer’s Company.

53 – the number of parish churches rebuilt by Christopher Wren.

6 – the number of land surveyors initially employed in the task of surveying the burnt area of the city, under the supervision of Robert Hooke. Each produced a map of the area they surveyed, which were then compiled into one manuscript.

14 days – the period given to the owners of damaged property to remove all debris and rubbish from their foundations, and to pile together any bricks and stones, so that the surveyors could measure their land (in an order issued by the Kings Council on 9 October 1666).

08 February 1667 – the date that the first Rebuilding Act was passed by parliament and given royal assent, outlining the form and content of rebuilding work to be undertaken (“No man whatsoever shall presume to erect any house or building great or small, but of brick or stone”).

40 feet – the minimum distance that buildings were to be built from the riverside of the Thames, and from the middle of the Fleet River.

3 years – the period within which (under the Rebuilding Act 1667) property that had been burnt or pulled down during the Great Fire had to be rebuilt on the same ground.

9 months – the length of the extension to that deadline that the Lord Mayor would serve to anyone not meeting the three-year deadline. If the extension was not met, the Lord Mayor was empowered to sell the property.

Staking Out The New City

4 – the number of men that the Court of Common Council (in a meeting on 13 March 1667) intended to appoint to be “surveyors and supervisors of the houses to be built [and to] forthwith proceed to the staking out the streets”. These were Robert Hooke, Edward Jerman, Peter Mills and John Oliver.

2 – the number of these who were actually sworn in the following day (14 March 1667). Jerman was absent and Oliver asked to be excused, but also offered to work for free to support Mills, whose health was failing (Mills died three years later, in 1670).

27 March 1667 – the date Hooke and Mills started the work of staking out the streets.

1,220 feet – the length of timber used for stakes in the first week.

6 – the number of carpenters employed.

7 – the number of labourers employed.

9 weeks – the period over which most of the staking-out was completed, although this work went on sporadically for another few years.

11 miles – the estimate of the total length of the streets staked out in the first nine-week period.

6,000 feet – the total length of timber used during the first nine-week period.

670 feet – the average length of timber used per week during the first nine-week period.

3 months – the length of imprisonment to be served by anyone ‘who wilfully pulled up a stake or boundary stone’.

£10 – the fine that could be issued for the same offence, in lieu of a prison sentence.

Did You Know?

A third punishment could be meted out any ‘man of mean condition’ caught tampering with the boundaries marked out by the survey; being ‘taken to the place of his offence and there whipped until the body be bloody’ (Calendar of State Papers, Domestic Series).

28 January 1668 – the date on which John Oliver was eventually formally appointed as the third city surveyor.

19 July 1670 – the date that Mills completed his last survey (his health already failing, he died three months later).

95% – the amount of the staking out work that had been completed by the beginning of 1672.

8,394 – the total number of foundations staked out by the surveyors.

£2,798 – the amount paid out for the surveyors’ services.

7 years – the approximate period of time Hooke was employed in the surveying work.

3,000 – the estimated number of foundations staked, measured and certified by Hooke himself.

30 minutes – the estimated average time to stake out a property.

£100 – the annual salary paid to the surveyors at the commencement of the work.

£150 – the annual salary the surveyors were paid from Lady Day (25 March) 1667.

£1,062 – the total salary received by Hooke (£1,062 and 10 shillings to be precise).

£1,500 – the estimate of the additional amount Hooke would have earned, from payments made by citizens for foundation certificates.

Compensating For Lost Land

Did You Know?

Some Londoners were going to lose land in the rebuild, land used to build new and wider streets. Each claimant therefore received an area certificate, which recorded their name, the site location, the aspects and dimensions of the boundary lines, and an account of the area of ground taken from them.

£600 – the amount paid to the first landowner (Richard Hodilow) as compensation for the loss of land, when ground in Cheapside was used for a new street (paid in early March 1668).

04 April 1667 – the date that Mills issued the very first ‘area certificate’.

7 months – the time between the end of the Great Fire and the first area certificate being issued.

22 January 1668 – the date the City Lands Committee was empowered by the Court of Common Council to agree compensation with the owners and tenants of land taken away in the rebuilding.

18 March 1668 – the date the Court of Common Council repeated their order, but clarified that the payment of compensation was to come from the ‘coal monies’ (the tax raised on coal).

16 July 1668 – the date that Hooke issued his first area certificate.

11 March 1687 – the date that Hooke issued the very last area certificate.

19 years – the period over which Hooke was engaged in administering compensation for lost ground.

21 years – the time after the Great Fire that the very last area certificate was issued.

Deciding Responsibilities

01 January 1668 – the date that the new Fire Court began, whose task it was to settle individual disputes over land and to arbitrate between property owners and their tenants over who would pay for the rebuilding of property.

Did You Know?

Most Londoners lived as leaseholders, renting their homes from the owners. Their leases required tenants to cover the full costs of any damage (and also to pay the rent for the full term of the lease, even if the property no longer existed). The trial and execution of Robert Hubert in October 1666, in making the fire an act of war, put the responsibility back onto the property owners. But a parliamentary report issues in January 1667 concluded that the fire was not a malicious act and so responsibility once again fell on tenants. Their obvious inability to cover the costs of rebuilding London led to the setting up of the Fire Courts, to better distribute the burden.

22 – the number of ruled parchment skins delivered to the first Fire Court, which met at Clifford’s Inn near Fleet Street.

1,500 – the number of sheets of paper delivered (3 reams).

300 – the number of quills delivered.

6 pints – the amount of ink delivered.

The rebuilding of the City will not be so difficult as the satisfying all interests, there being so many proprietors. – Sir Nathaniel Hobart, Judge, 13 September 1666.

2 years – the period that the first Fire Court operated, stopping on 31 December 1668.

14 – the number of judges who heard petitions from landlords and tenants during the first period.

£0 – the amount that each judge was paid for their work on the Fire Courts – they each worked for free.

800 – the number of cases the Court heard during this first period.

120 days – the number of times the court sat in the first year.

4 – the average number of petitions heard each day.

383 – the number of cases heard by one judge alone, Sir Thomas Tyrell, a Justice of the Common Pleas.

3 – the number of distinct periods the Fire Court operated (the second and third being 1670-1672 and 1673-1676.

25 February 1676 – the date the Fire Court was finally wound up.