“A hell of confusion and torment”

Having started with a single fire the previous morning, by Monday the fire was already out of control and destroying around 100 houses every hour, the flames still being fanned by the strong winds that blew from the north east. Here we recount some key details from the second day of the Great Fire of London.

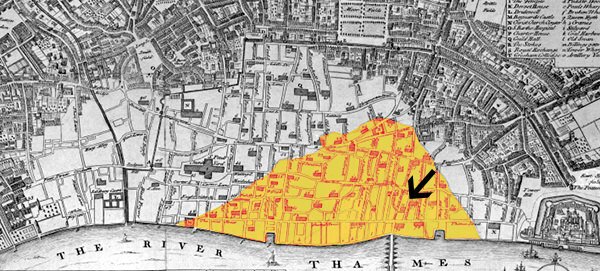

Above: Map showing the extent of the fire at the close of Monday (arrow points to Pudding Lane, where the fire started).

4.00 a.m. – the time at which an acquaintance of Pepys (Lady Elizabeth Batten) sent a cart with which he could carry away all of his “money, and plate, and best things”, along with the notebooks containing his diary, to a friend’s property in Bethnal Green, outside of the city walls. Pepys travelled in the cart, still in his night-gown.

5.00 a.m. – the time that the last copy of the London Gazette was published before the presses were abandoned on Monday evening.

9.00 a.m. – the time that James, Duke of York, took charge of firefighting operations and set up a number of fire command posts around the City, press-ganging men into teams of firemen.

8 – the number of command posts set up by the Duke of York upon taking command of firefighting efforts, in and around the city, five outside of the city walls (Cow Lane – Shoe Lane – Fetter Lane – Clifford’s Inn Gardens – Temple Bar) and later in the afternoon, three inside (Aldersgate – Coleman Street – Cripplegate).

3 – the number of courtiers placed in charge of each post; they were given autonomy to demand demolitions of buildings to create firebreaks.

30 – the number of foot soldiers placed at each fire post.

100 – the number of civilians at each post.

10:00 a.m. – the approximate time that the fire reached the wealthiest part of the City, the area around Lombard Street and Gracechurch Street (the street where Lord Mayor Bludworth had his home).

12:00 pm – the approximate time that James Hickes, postmaster, had to abandon the General Letter Office in Posthouse Yard and escape with his family. The following day he set up a temporary post office in the Golden Lion Inn, where they had sheltered overnight.

The houses tumble, tumble, tumble with a great crash, leaving the foundations open to the view of the Heavens. – Thomas Vincent, puritan preacher, ‘God’s Terrible Voice in the City’, 1667.

8 – the number of gates in the City wall, which witnessed scenes of bottlenecks and near-panic on the Monday, as refugees desperately tried to escape the fire (clockwise, west to east: Ludgate, Newgate, Aldersgate, Cripplegate, Moorgate, Bishopsgate, Aldgate, Postern Gate – see map on Resources page.).

Did You Know?

Lord Mayor Bludworth appears to have left the city by the Monday, as there are no accounts of the firefighting thereafter that mention him.

2.00 p.m. – the approximate time that the Royal Exchange, centre of commercial and financial activities in London, caught fire.

3,000 – the number of merchants displaced when the Royal Exchange burnt down.

…owners shove as much of their goods as they can towards the gates. Everyone now becomes a porter to himself, and scarcely a back, either of man or woman that hath strength, but had a burden on it in the street. – Thomas Vincent, puritan preacher, ‘God’s Terrible Voice in the City’, 1667.

3.00 p.m. – the approximate time that the city gates were closed to incoming traffic, allowing only outgoing people and carts, due to the near-panic and chaos being witnessed. At times it was taking hours to pass through the gates, so congested had they become.

Did You Know?

There was no police force in 1666. That fact, plus the general confusion and panic caused by the fire, allowed many opportunities for London’s thieves and looters, many of whom escaped from prisons deserted by their guards.

1829 – the year the Metropolitan police service was established in London; a full-time professional police force that replaced the part-time and largely unpaid parish constables.

What a hell of confusion and torment in the rage of fire and wind. – Edward Waterhouse, A Short Narrative of the Late Dreadful Fire in London, 1667.

2 shillings – the cost of hiring a cart the day before the fire.

£11 – equivalent cost in modern money [?].

£40 – the cost of hire on the Monday of the fire, as their owners exploited the opportunity to make money from London’s wealthier residents, desperate to get their valuables away from the flames.

£4,500 – equivalent cost in modern money [?].

Did You Know?

According to some accounts, cart and boat owners from up to 10 miles around flocked to the city, attracted by the opportunity to earn well from the misfortune of others. London’s wealthier residents were willing to pay handsomely to have their belongings carried to safety.

Above: Detail from an engraving depicting the Fire of London, by James Stow, produced between 1792-1823 © Trustees of the British Museum.

£400 – the amount one wealthy merchant was reported to have paid to have his goods transported away from the blaze.

50 miles – the distance that the smoke had stretched by the Monday.

Did You Know?

Pepys lived just a few streets away from Pudding Lane. His house on Seething Lane survived the fire, but Pepys took the precaution of moving valuable property out of the city. He also buried some in a pit in his garden, including wine and parmesan cheese (an expensive Italian luxury in 1666).

4:00 pm – the time by which Lombard Street, the financial centre of the city (and home to many of England’s wealthiest men) succumbed to the fire, which was moving north toward the fashionable shopping district of Cornhill.

200lb – the weight of molten silver recovered from the Mercer’s Hall in Cheapside after the fire.

1 mile – the estimated width of the front line of the fire by Monday evening, described by Samuel Pepys as “one entire arch of fire…above a mile long”.

The noise and the cracking and thunder of the impetuous flames, the shrieking of women and children, the hurry of people, the fall of towers, houses, and churches, was like a hideous storm; and the air all about so hot and inflamed. – Samuel Pepys.

100 feet – the height that the wall of flames reached in places.

Did You Know?

The Guildhall, the city government’s grand palace, was almost completely destroyed when the fire reached it on Monday. However the vault and it is a valuable contents – centuries of records and parchment relating to London’s laws and history – survived.

50% – the approximate amount of the City of London destroyed by Monday evening.

500% – the approximate increase in the number of buildings destroyed on Monday compared to Sunday, as the fire spread upwards and outwards from the epicentre.

Did You Know?

Further away from London, some people assumed England was under attack when letters stopped arriving (other than by word of mouth, the mail was than the only way of communicating). The sudden abrupt end to the mail was actually the result of the General Letter Office succumbing to the fire.

10 miles – the extent of the area illuminated by the fire at night, as recounted by the diarist John Evelyn on 03 September 1666.

Oh, the miserable and calamitous spectacle – John Evelyn, describing the scenes of refugees making camp in the fields north and east of the city walls.