Overview of the Great Fire

Here we present a selection of the key facts relating to the Great Fire of London. For a fuller selection of fascinating facts and figures please navigate to the relevant page.

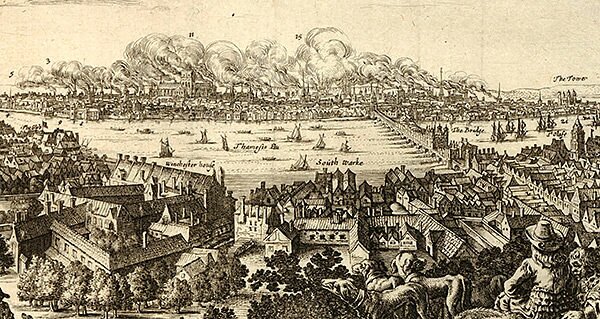

Above: Depiction of the Great Fire of London, from a broadside titled the ‘Popish Damnable Plot’, 1680 © Trustees of the British Museum.

Key Facts About The Fire

5 – the number of days that the great fire burned (although smaller fires flared up for days afterwards).

5/6 – the amount of the city that was consumed by the Great Fire.

1 1/2 miles – the length of the area affected by the fire.

1/2 mile – the breadth of the area affected.

1,700 °C – the approximate height of the temperature in Pudding Lane (3,092 °F) based upon fragments of melted pottery excavated there. At this temperature, even stone will melt.

6 – the number of reported deaths (however deaths were not recorded for the poor or middle classes, whilst the remains of victims would have been completely destroyed in the heat of the fire).

£10,000,000 – the estimated cost of the fire, although this was probably much higher when the impact of the fire upon trade in the rest of England is considered.

£1.1 billion – the equivalent amount in modern money [?].

25% – the proportion of citizens who never returned to London following the Great Fire, revealed by a census of the population recorded seven years later, in 1673.

Above: The area affected by the fire, overlaid on a map showing the City walls, gates, and locations of Pudding Lane, Pepys home, St Pauls Cathedral, and Moorfields (image via Wikimedia Commons).

13,200 – the number of houses destroyed.

87 – the number of parish churches destroyed.

1/6 – the proportion of Londoners living within the City of London.

100,000 – the approximate number of people who had to evacuate the city, some south across the Thames, others north to places such as Clerkenwell, Finsbury and Islington (now part of the enlarged London).

80,000 – the number of those residents rendered homeless.

1 – the number of people officially tried and executed as responsible for the fire, Robert Hubert. He was innocent, however.

Sunday 02 September

1:00 a.m. – the approximate time the Great Fire started was discovered, in a bakery on Pudding Lane owned by Thomas Farriner.

Did You Know?

Londoners were not overly alarmed by the fire to begin. In a crowded city of wooden homes, lit by the naked flames of candlelight and with open fires for heat, cooking and drying clothes, such fires were not unusual.

300 – the number of houses estimated to have burned down by 07:00 a.m., according to reports given to Samuel Pepys by his maid. Pepys then went to inspect the extent of the fire.

Having stayed, and in an hour’s time seen the fire rage every way, and nobody, to my sight, endeavouring to quench it, but to remove their goods…I to Whitehall, and there up to the King’s closet in the Chapel. – Samuel Pepys.

11:00 am – the approximate time that Pepys arrived at Whitehall to report the fire to King Charles II. The king instructed Pepys to find Lord Mayor Bludworth and order him to start pulling down houses to create a firebreak.

Did You Know?

Conditions at the time of the fire helped its spread and ferocity. There had been no rain for some weeks, with the preceding months seeing a “long and extraordinary drought” according to the diarist John Evelyn. So the predominantly wooden buildings were exceptionally dry. Adding to this, strong winds from the east fanned the flames.

3:00 pm – the approximate time that the king and his brother, James, Duke of York, sailed along the Thames to view the fire.

3 furlongs – the distance (600 m) that burning embers were carried on the wind, witnessed by William Taswell, then a schoolboy at Westminster School.

All over the Thames with one’s face in the wind you were almost burned with a shower of firedrops…so as houses were burned by these drops and flakes of fire, three or four, nay five or six houses, one from another. – Samuel Pepys.

100 – the estimated number of houses burning every hour by Sunday afternoon.

Did You Know?

When the fire reached the northern bank of the Thames it was further fuelled by the warehouses of “oil, hemp, flax, pitch, tar, cordage, hops, wine, brandies and other materials favourable to fire [and wharves storing] coal, timber, wood &c.” (Edward Waterhouse, ‘A Short Narrative of the Late Dreadful Fire in London’, 1667).

Monday 03 September

9.00 a.m. – the time that the Duke of York took charge of firefighting, setting up a number of fire posts around the City and press-ganging men into teams of firemen.

10:00 a.m. – the approximate time that the fire reached the area of Lombard Street and Gracechurch Street (the street where Lord Mayor Bludworth had his home), the wealthiest part of the City.

Above: Detail from an engraving depicting the Great Fire seen from the south, with people on a hill looking across Southwark and the Thames to the burning city, by Justus Danckertsz, 1666 © Trustees of the British Museum.

2.00 p.m. – the approximate time that the Royal Exchange, the commercial and financial centre of London, burned.

50 miles – the distance that smoke from the fire reached during Monday.

3.00 p.m. – the approximate time that the city gates were closed to all traffic coming in to the City, due to the chaos and near-panic conditions being caused by the congestion (at times it took hours to pass through the gates).

1 mile – the width of the front line of the fire by Monday evening, as estimated by witness Samuel Pepys.

50% – the approximate amount of the City destroyed by fire by Monday evening.

10 miles – the size of the area illuminated by the fire at night, recounted by the diarist John Evelyn.

Tuesday 04 September

5:00 a.m. – the approximate time that the King and Duke of York rode into the City to give encouragement to the exhausted people fighting the fire.

6:00 a.m. – the approximate time that the order banning carts from entering the City gates was withdrawn.

12:00 p.m. – the approximate time that fire reached the areas of Ludgate and Newgate, destroying the prisons there. Elsewhere in the City, the Duke of York was almost overcome by the fire.

Above: Ludgate burning in the Great Fire of London, with St Pauls Cathedral seen in the background. Hand-coloured etching by William Russell Birch, 1792 © Trustees of the British Museum.

30 miles – the distance at which scraps of scorched silk travelled on the wind (found in Beaconsfield, to the west of London).

6:00 p.m. – the time the fire reached the area of Temple.

100 yards – the distance at which the heat from the fire was intolerable, such was the intensity of the flames.

8:00 pm – the approximate time that St Paul’s Cathedral caught fire.

Did You Know?

At one point on Tuesday night, so dense and charged was the pall of smoke that hung above London that a thunderstorm broke out, sending lightning down around St Paul’s Cathedral. It lasted for some minutes but no rain fell.

50 miles – at its height, the distance at which the fire could be seen (80 km); there were reports of people in Oxford being able to see the blaze.

10:00 p.m. – the approximate time that buildings in the area of Somerset House were pulled down, in a desperate (and successful) attempt to save Whitehall.

18 – the approximate number of hours that the Duke of York spent engaged in fire-fighting efforts on Tuesday.

11:00 p.m. – the approximate time at which the strong winds that had fanned the flames since Sunday morning finally began to reduce in intensity.

Did You Know?

As the winds reduced, they also changed direction, allowing the fire to start moving toward the Tower of London, where the stores of gunpowder were kept. A decision was taken to save the Tower by blowing up surrounding buildings, and in case this wasn’t sufficient, to evacuate the gunpowder barrels (and the money, gold, silver and jewels that had been moved to the Tower for safekeeping) away from the scene.

Wednesday 05 September

6:00 a.m. – the approximate time the king evacuated Whitehall, leaving for Hampton Court, and the Duke of York returned to the streets, later organising men, women and children to salvage the Court records from the rolls Chapel.

7:00 a.m. – the time that Pepys arrived back in London (having evacuated his gold to Woolwich), discovering that his home in Seething Lane had survived the fire (due to the blowing-up of nearby houses to create a firebreak), and climbing the steeple of Barking Church to survey the scene of destruction, “the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw”.

12:00 p.m. – the approximate time the fires around Holborn Bridge were extinguished.

50,000 – the number of French and Dutch said to be heading toward the fields outside the city walls to kill and steal from the refugees there, leading to angry mobs heading into the city to attack any foreigners they found.

10:00 p.m. – the time that one seaman, Richard Rowe, bravely climbed onto the burning roof of the Middle Temple Hall to beat out the flames.

1 – the number of major fires that still burned on Wednesday evening, in the area around Bishopsgate. It was eventually extinguished just before dawn.

After the Fire: Rebuilding London

6–8 months – the estimated period after the fire that the rebuilding is likely to have commenced, with the arrival of spring in 1667.

13 September 1666 – the date that a royal proclamation was issued which prohibited rebuilding until new regulations had been officially formulated and issued.

3 – the number of major project proposals put forward for the rebuilding of London (proposals from Evelyn, Hooke, and Wren). All were rejected, however, and a simplified plan followed.

Above: Detail from an engraving depicting Christopher Wren presenting his plan for rebuilding London to King Charles II © Trustees of the British Museum.

53 – the number of parish churches that Christopher Wren rebuilt.

08 February 1667 – the date the first Rebuilding Act was passed by parliament. It outlined the form and content of rebuilding work to be undertaken, including the requirement that all new buildings were made of brick or stone.

11 miles – the estimate of the length of the streets staked out for rebuilding in the first nine-week period of this work, having commenced in March 1667.

95% – the amount of staking out completed by the beginning of 1672.

Did You Know?

Some Londoners lost land in the rebuilding of the City, as roads were widened or repositioned, and so each claimant received an ‘area certificate’, recording the area of ground taken from them, and compensation for their losses.

21 years – the time from the end of the Great Fire that the last area certificate was issued.

800 – the approximate number of buildings rebuilt by the end of 1667.

12–15,000 – the approximate number of buildings rebuilt by 1688, 12 years after the fire.

35 – the number of years the rebuild of St Paul’s cathedral took.

London in 1666

100,000 – the common estimate of the size of the population of London in 1666.

10 months – the period of time that London had been under drought conditions, with a long, hot summer preceding the fire.

6 to 7 – the typical number of storeys in timbered tenement houses, the upper floors overhanging the streets below, leading to a largely cramped and closed-in City.

1665 – the year that the great plague struck London (at the time of the fire the plague had died down in London but was still raging across England).

15-20% – the proportion of London’s population who had died from the plague.

A History of Fire

The Great Fire of 1666 was not the first time London had witnessed major conflagrations. Here are some of the other key occurrences from London’s history.

1,606 – the number of years prior to the Great Fire that London was first destroyed by fire. In A.D. 60, Queen Boudicca and her Iceni tribe burned the Roman city of Londinium.

450 – the number of years prior to the fire that the last fire to be called the ‘Great Fire of London’ occurred (1212).

1633 – the year that a fire destroyed houses on London Bridge.

1643 – the year another fire caused extensive damage to London.

£2,880 – the cost of the damage caused in the 1643 blaze.

1650 – the year the gunpowder barrels being stored at a premises in Tower Street exploded and started a fire.

7 – the number of barrels.

41 – the number of houses rendered uninhabitable by the resulting blaze.

Did You Know?

Fires were not uncommon in 1666, but were usually caught before they spread and caused too much damage. They were fought using either water or by demolition (pulling buildings down to create firebreaks; gaps to stop the fire spreading). Fire hooks (long poles with hooks on the end) were typically used to pull down buildings, but gunpowder was also used on occasion, especially to bring down taller buildings.