“London was, but is no more”

Five days after a single small house fire began in the bakery on Pudding Lane, the City of London stood in ruins, with most of the population homeless and almost incalculable damage done to London’s property, trade, and above all, people. Here we recount what is known about the destruction wreaked by the fire, and the immediate aftermath.

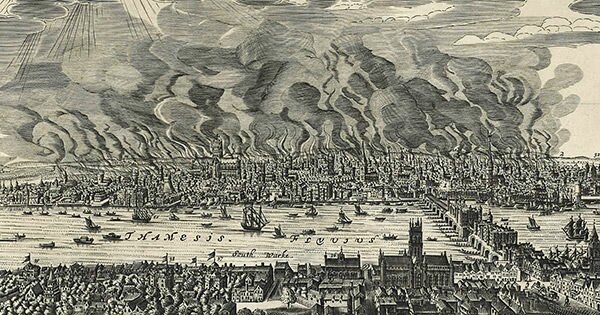

Above: Detail of an etching from a contemporary Dutch broadside on the Great Fire of London, 1666 © Trustees of the British Museum.

26 – the number of wards into which the City of London was divided, each represented by an Alderman.

15 – the number of these wards that were completely destroyed, with 8 more partially destroyed.

5/6 – the amount of the city consumed by the fire.

13,200 – the number of houses destroyed.

87 – the number of churches destroyed.

52 – the number of Livery Company halls destroyed in the fire.

8 – the number of Livery Company halls that survived the fire intact (the halls of the armourers, bricklayers, carpenters, cooks, glovers, ironmongers, leather-sellers, and upholsterers).

4 – the number of stone bridges destroyed (over other brooks and rivers, not the Thames).

460 – the number of streets that burned in the fire.

Much terrified in the nights nowadays, with dreams of fire and falling down of houses. – Samuel Pepys.

80% – the approximate percentage of City of London residents rendered homeless (80,000).

3 – the number of city gates destroyed (of 7) – Aldersgate, Ludgate and Newgate.

£10,000,000 – the estimated cost of the fire (probably much higher than this considering the fire’s impact upon trade in the rest of the country).

4 days – the period after the great fire was extinguished that the refugees who had camped in the open fields north and east of the city walls had almost all dispersed. Shanty towns appeared inside and outside the walls, whilst some constructed rudimentary shacks where their homes once stood. Others – especially pregnant women and the sick – were given refuge in any remaining churches, halls, taverns and houses, or in camps set up by the army.

25% – the proportion of London’s citizens who never returned after the fire, according to a census taken seven years later, in 1673.

3 weeks – the period of time that Bills of Mortality (the record of deaths in London) went unpublished, due to the printing press used to create them being burnt when Parish Clerk’s Hall succumbed to the flames. This meant that details of those killed in the fire went unrecorded (Great Fire of London deaths).

London was, but is no more. – John Evelyn.

9 September 1666 – the day rain finally fell on London, extinguishing some smaller fires but also turning the ash into a quagmire of mud (the rain was not sufficient to end the drought, which would last for another month).

17 September 1666 – the date Pepys recorded seeing fires reigniting.

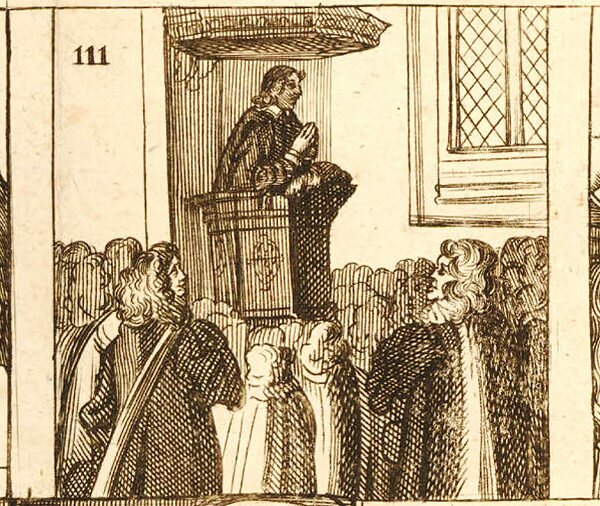

10 October 1666 – the date on which a ‘day of fasting and humiliation’ was observed, to implore God to take mercy and forgive the nation it sins. A collection was taken, to raise money for the victims of the fire, in every church in England and Wales (although the sum collected was modest, as plague still affected many parts of the country).

Above: Depiction of the a cleric preaching on a day of fasting and humiliation, from a broadside titled the ‘Popish Damnable Plot’, 1680 © Trustees of the British Museum.

Did You Know?

A special prayer was used on this day and continued to be used each year on 2 September, right up until 1859.

£12,000 – the value of the fund from which destitute Londoners could apply for financial aid.

£800 – the amount that one Londoner requested to rebuild her house.

£10 – the amount she actually received from the fund.

40 – the number of days after the great fire ended that the drought also ended, with a major downpour that started on 10 October 1666 (coincidentally the same day as the ‘day of fasting’).

10 – the number of days the rain continued (remarkably, even this prolonged spell of wet weather was insufficient to stop new fires breaking out amid the ruins).

£103 15s 4d – the cost of the clearance work, undertaken by contractors, which commenced in December 1666.

£100 – the amount of this cost paid by the king.

3 months – the period after the great fire ended that coals were found in one cellar, still burning (on 30 November 1666).

01 December 1666 – the date Pepys recorded seeing a fire start in the cellar of ruin in Tower Street, as winds reignited logwood.

14 December 1666 – the date Pepys recorded seeing smoke still rising from some ruins as he travelled across the city to Whitehall.

17 January 1667 – the date Pepys recorded observing “still in many places the smoking remains of the late fire”.

28 February 1667 – the date Pepys again recorded seeing smoke from the ‘late fire in the city’.

16 March 1667 – the date Pepys recorded “I did see smoke remaining, coming out of some cellars from the late great fire now about six months since “.

Crime In The City

Though constables, the Trained Bands and the militiamen patrolled the streets, the ruin was so great and the confusion so bewildering that it became no difficult task for the robber and the assassin to escape undetected to his haunts in safe possession of his booty. – Alexander Charles Ewald, ‘The Great Fire of London’, Gentlemen’s Magazine vol 250, 1881.

1 shilling – the threshold (12 pence) above which thefts could be punished by hanging.

£5 – the approximate equivalent sum in modern money [?].

8 – the number of days offered as an amnesty to thieves, allowing them to bring “any plate jewels, money, household stuff, goods or merchandize” stolen or looted to the Finsbury armoury, without fear of punishment. Announced a few days after the fire, it is not known how many thieves responded.

£20,000 – the amount of the funds collected for the victims that went missing, according to Lord Mayor Sir William Bolton (the man who replaced Bludworth). In fact, he was himself accused of withholding the money, and subsequently convicted of embezzlement.

£1,800 – the amount that Bolton was accused of withholding (Bolton ended up very poor and in 1677 was given a pension of £3 per week by the Court of Common Council).

The greatest piece of roguery that they say was ever found in a Lord Mayor. – Samuel Pepys, 3 December 1667.

£100,000 – the amount that a former sheriff of the city was fined in 1682, having publicly claimed that the Duke of York was responsible for the Great Fire.

Lessons Learned

4 – the number of sections into which the city was divided for firefighting efforts.

800 – the number of buckets to be available in each of the four sections.

2 – the number of times that fireplaces had to be safety-inspected each year.

1680 – the year that London’s first Fire Brigade came into existence, funded by the insurance companies (the first publicly funded fire service was created in 1861, following the Tooley Street fire).

The Changing Population

300,000 – the number of people living in London (the City and outlying suburbs) at the time of the Great Fire.

600,000 – the population of London by 1700.

25% – the proportion of London’s citizens who never returned after the fire, according to a census taken seven years later, in 1673.